As if there's not enough to worry about in the political realm, I came across

this article about my chosen profession, general surgery. (I'm pretty sure you can't read it without a password, at least at Medscape. It's by a David W Page, MD, FACS, and originally appeared in

The Southern Medical Journal,

South Med J. 2010;103(12):1232-1234). While it's not really anything I didn't know, it crystalizes what will surely be an increasingly severe problem. The following is from the part titled "The Consequences of Inexperience":

... it is crucial to reassess the challenges, cognitive and technical, that face our trainees as they enter private practice. To reach a level of basic competency in performing most laparoscopic operations–not to become a master surgeon–the learning curve (number of cases versus complications) requires between 30 and 50 cases or repetitions. For laparoscopic hernia repair, the number is closer to 100 to 200 cases. Laparoscopic groin hernia operations are true ergonomic and technical challenges. Despite this fact, most graduating residents do ten or fewer casesduring their training. These trainees are, by definition, not competent to perform laparoscopic hernia repairs but do them in practice.

During the most frequently performed laparoscopic operation (cholecystectomy), the incidence of common bile duct injury continues to fall as far out as with the surgeon's experience of 200 cases. Graduating residents do about 84 cases in their five years of training. Bell et al conclude, "Even for more commonly performed procedures, the numbers of repetitions are not very robust, stressing the need to determine objectively whether residents are actually achieving basic competency in these operations."

In a related presidential address entitled, "Why Jonny Cannot Operate," the same Richard H. Bell, MD, stated that chief residents in surgery spend between 1148 and 2753 hours performing the essential 121 and other operations. This is only 6 to 14% of the resident's total working time during a five-year training program. ... Clearly, surgical residents are not exposed to an adequate number of cases nor do they practice enough to achieve minimum competence in a wide range of surgical procedures...

How we train surgeons remains part of the problem. In 2007, a survey revealed that there is a wide disconnect between what teaching surgeons felt residents needed to do to prepare for a case and what the residents felt was proper preparation...

... the system remains weighted with inertia. All of which leaves one to react with little surprise to the fact that 13% of today's general and vascular surgery patients develop complications and 2% die postoperatively.

I can't vouch for those last numbers, and they're way higher than I saw in my practice, or in those of surgeons around me. WAY higher. But from my several friends in academic surgery, the trend toward less and less rigorous experience in a training program is inarguably true.

Rightly or wrongly -- depending on whether you were one of my patients, or are a current student or trainee -- when I learned to be a surgeon (the process never stops; but I refer to residency here), there were no limits on hours spent at work other than the number of hours in a day, days in a week, weeks in a month. Nor was there much in the way of touchy-feely, unless you count the occasional rap on the knuckles with a surgical clamp. Techniques of surgery were, in some sense, the least of it: pounded in hourly, daily, at conferences, on rounds, in the operating room was the sense of personal responsibility, of commitment. Doing everything necessary to be able to make a proper judgment, being held accountable for anything less than perfection, taking care of what needed doing no matter if you (theoretically) had the night off or not. In my several years of training, it was far less than half of nights that I spent at home. Many were the rotations in which I got out of the hospital only every other weekend and no weekdays at all. In my final year, as Chief Resident on the trauma service, I didn't go home for two straight months.

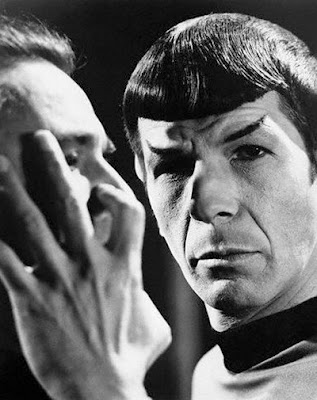

I'll leave it to others to argue whether such training -- the way it was since William Halsted picked up a knife and until only a handful of years ago -- was inhuman, brutal, dangerous, or necessary. Whatever else is true, I came out of it with the ability to operate safely, to know when to operate, when not, which operation to do, and which not. Perhaps more important, I had a sense of commitment -- probably based on an unrealistic sense of my own importance and indispensability in the care of my patients -- that had me making rounds several times a day, day on, day off. As

Mr Miyagi would say.

I don't blame the trend entirely on reduced training hours. I recognize there's more to know every year, and that assimilating what's known and what's coming down the pike is increasingly impossible. Sub-specialization is the inevitable consequence both of receiving less initial training and of the desire to limit what one does, in order to become and remain expert, and to de-stress one's life. But I loved being a general surgeon, able to provide a wide range of care, to be for some their "family surgeon." To be, as we liked to imagine in training, "an internist who can operate."

Those days are surely on their way to being irrevocably gone, and given the fact that we're never going back to the kind of training I had, I think it's best: we'll have some surgeons capable of doing a few things well, leaving much of the post-op care to someone else, and that's all we can hope for. The article also refers to the decreasing numbers of people choosing to become surgeons, and, as reimbursement continues to decline and various annoying paper requirements continue to increase, I don't see that changing, either.

The author includes mention of the problem of burnout -- which I experienced -- and ends with a few suggestions for changing training. To me, they ring pretty hollow, in part because the list assumes mostly laparoscopic procedures (which lend themselves to recording and reviewing), and because, given the time constraints, I don't see much of any of it happening in a meaningful way. Too, it seems to ignore the idea of being a physician along with being a surgeon. Unimportant? I don't think I know anymore.

Bell has suggested seven recommendations to improve surgical education:

- Insure that the trainee has undergone both cognitive and skills training (simulation) with the procedure before going to the operating room.

- Have the resident assessed (using validated metrics) before going to the operating room (OR) so the faculty surgeon will know the resident possesses a basal level of ability.

- Rehearse the operation on a simulator and discuss with the faculty member where major intra-operative decisions need to be made before going to the OR.

- After the operation, debrief with the faculty member and review areas of accomplishment and parts of the operation that need more work.

- Grade the trainee's performance and file the report in the resident's portfolio.

- Have the resident review a video of the case and practice in the skills lab those maneuvers proven to be difficult for the trainee.

- Keep a national database of resident experience for the purpose of research and norm-setting.

Near the conclusion is this uplifting view of the future:

These and other related issues conspire to make quality surgical care problematic for Americans in the future. Without change, we will almost certainly witness the disheartening 1990 prophesy by Griffen and Schwartz who stated, "Eventually, our society will be "served" by a medical community that is less talented and definitely less interested in providing medical services in the tradition of its predecessors."

In that spirit, here's my personal plan, as I view my potential patienthood: don't get surgically sick. And if you do, aided as necessary by decent pain medication and gin, and if all else fails, by a hose to the tailpipe of your car, let nature take its course.

If you're a teabagger, think of the money you'll remove from government spending, just like you want. (I'll avoid any sort of cheap reference to the gene-pool.)

And with that, I'm off to the OR to assist in a cancer operation. Have a healthy day.